17 January 2026

A common question people ask is: If we have vaccines for infections such as polio, COVID-19, or hepatitis, why don’t we have a simple vaccine for cancer? The answer lies in a fundamental difference; cancer is not a single disease and does not arise from an external infection. Instead, it develops from our own cells as they gradually acquire changes that allow uncontrolled growth, making cancer cells far more difficult for the immune system to recognize as harmful.

Traditional vaccines train the immune system to attack foreign invaders. Cancer cells, however, closely resemble normal cells and can actively suppress immune responses, allowing them to escape detection. This biological complexity is the main reason why developing effective cancer vaccines has been far more challenging than creating vaccines for infectious diseases.

Despite these challenges, significant progress has been made. Modern cancer vaccines are designed to teach the immune system to recognize subtle differences between healthy and cancerous cells. Unlike preventive vaccines, most cancer vaccines are therapeutic, meaning they are intended to treat existing disease rather than prevent it. Advances in immunology, genomics, and vaccine technologies have revitalized this field after earlier clinical setbacks.

How Cancer Vaccines Work

Cancer cells often display abnormal proteins, known as tumour-associated antigens or neoantigens, that distinguish them from normal cells. Cancer vaccines expose the immune system to these markers, enabling immune cells particularly T cells to better identify and eliminate cancer cells. Some vaccines are designed for broad use, while others are highly personalized and tailored to the genetic makeup of an individual patient’s tumour.

Types of Cancer Vaccines

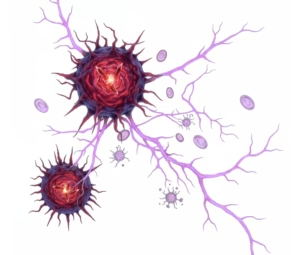

Several vaccine platforms are currently being explored, including peptide and protein vaccines targeting known cancer antigens, whole-cell or tumour lysate vaccines that present multiple targets, and dendritic cell vaccines that harness the body’s own immune cells. More recently, mRNA-based vaccines have gained attention due to their flexibility, speed of development, and favourable safety profiles.

Personalized and Combination Approaches

One of the most promising advances is the development of neoantigen vaccines, which target mutations unique to cancer cells, improving immune specificity while minimizing damage to healthy tissue. However, because tumours can suppress immune responses and adapt over time, vaccines alone are often insufficient especially in advanced cancers. As a result, current strategies increasingly combine cancer vaccines with other treatments, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors or targeted therapies, to enhance effectiveness.

Looking Ahead

Cancer vaccine development is moving toward a future of precision immunotherapy, where treatments are tailored to individual tumour biology. While cancer vaccines are unlikely to replace existing therapies, they are emerging as important components of combination treatment strategies aimed at achieving durable disease control with fewer side effects. With continued technological advances and deeper insights into tumour–immune interactions, cancer vaccines are steadily transitioning from experimental concepts to clinically meaningful therapies.