3 January 2026

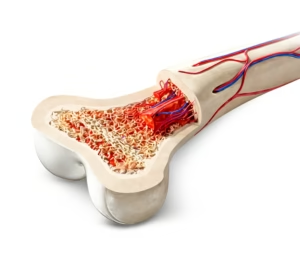

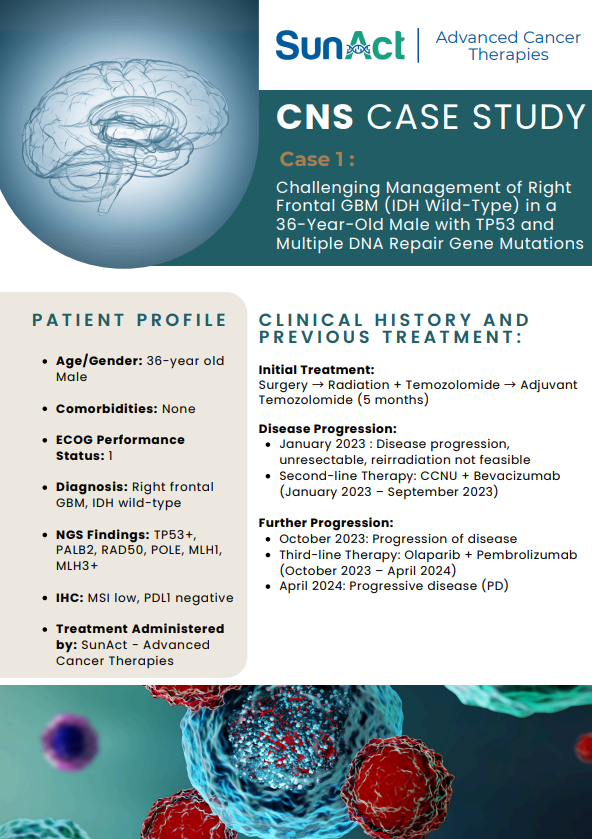

Multiple myeloma presents a unique challenge in blood cancers. This disease affects plasma cells—specialised white blood cells that normally produce antibodies to fight infections. When myeloma develops, these cells multiply uncontrollably in the bone marrow, producing abnormal proteins that damage bones, kidneys, and the immune system.

Unlike many blood cancers where transplant aims for cure, the role of transplantation in myeloma is more nuanced. Doctors view it as a powerful tool to achieve deep, lasting remission and extend survival, even though most patients eventually experience disease recurrence.

Myeloma predominantly affects older adults, typically those over 60, though younger patients are increasingly diagnosed. Symptoms often develop gradually—bone pain, particularly in the back or ribs, fatigue from anaemia, frequent infections, and sometimes kidney problems. Many patients discover their diagnosis through routine blood tests that reveal abnormal protein levels or elevated calcium.

Modern myeloma treatment follows a sequential approach. Initial therapy typically combines several drugs—novel agents like bortezomib or lenalidomide with steroids. Once the disease responds and myeloma protein levels drop significantly, eligible patients proceed to autologous stem cell transplant.

The transplant process for myeloma has become highly standardised. After initial treatment response, doctors collect stem cells during a procedure that takes several hours over one or two days. Patients then receive high-dose melphalan chemotherapy—the standard conditioning regimen for myeloma—followed by infusion of their stored stem cells.

Unlike transplants for leukaemia or lymphoma, myeloma patients usually spend less time in hospital—often just two to three weeks. The conditioning is intense but generally better tolerated, and recovery tends to be quicker. Most patients return home within a month and resume normal activities within two to three months.

The benefits of transplantation in myeloma are well-established. Studies consistently show that transplant deepens the response to initial therapy and extends the time before disease progression. Patients who achieve complete remission after transplant may enjoy several years without active disease, and some remain in remission for a decade or longer.

However, myeloma biology means that cure remains elusive for most patients. The disease typically returns eventually, requiring additional treatment. This reality has shifted the treatment paradigm towards viewing myeloma as a chronic condition managed through sequential therapies rather than a single curative treatment.

Recent advances have added new dimensions to myeloma transplantation. Maintenance therapy—ongoing treatment with drugs like lenalidomide after transplant—further extends remission. Some patients may even undergo a second autologous transplant if disease returns years later.

The decision to proceed with transplant involves careful consideration of age, overall health, disease characteristics, and patient preferences. Whilst physically demanding, autologous transplant remains the standard of care for eligible myeloma patients, offering the best chance for prolonged disease control and quality of life.

For myeloma patients, transplantation represents not the end of treatment but a crucial milestone in a longer journey—one that increasingly offers years of good health and normal life.