3 January 2026

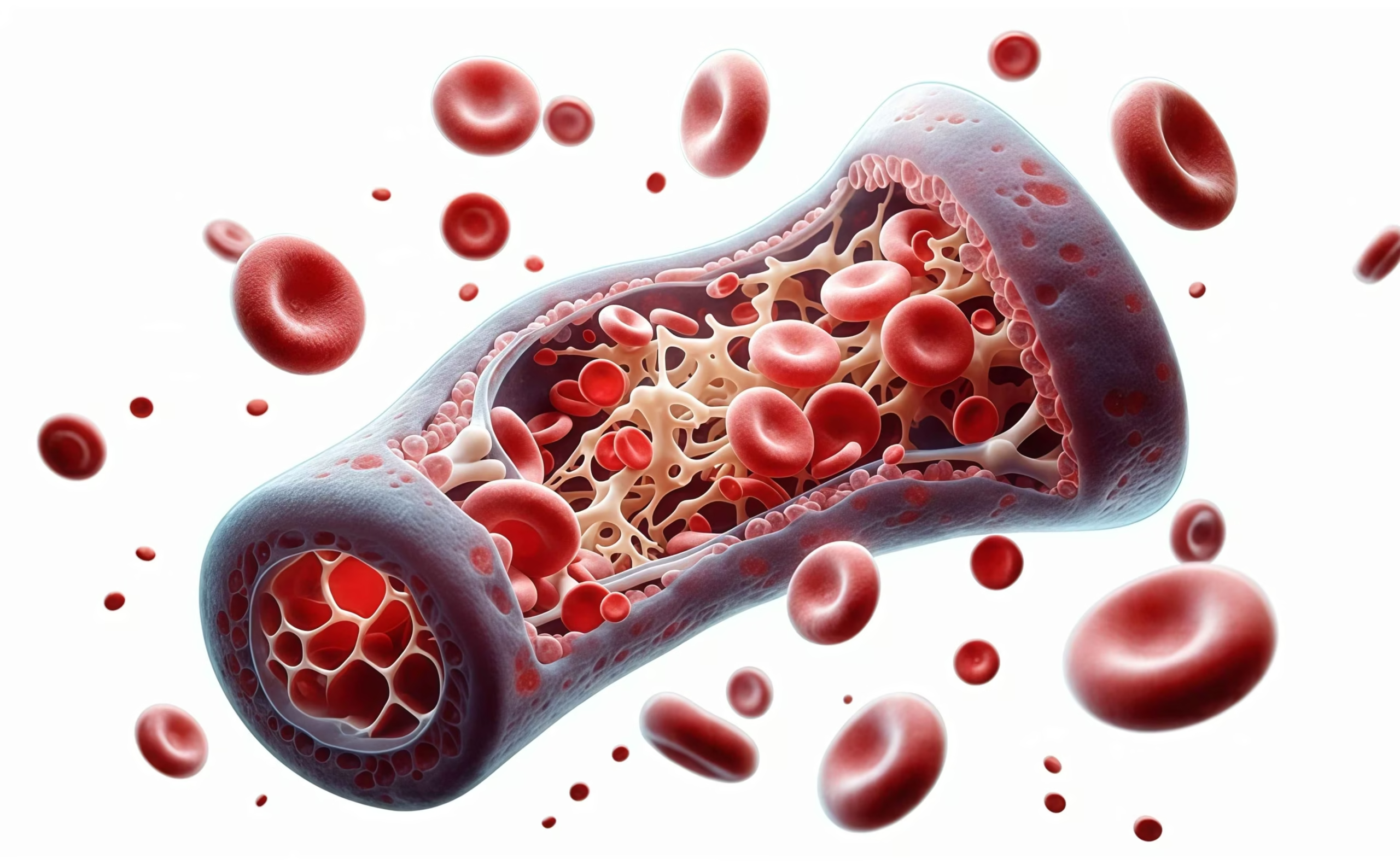

Aplastic anaemia stands apart from other blood disorders. Rather than producing abnormal cells, the bone marrow simply slows down or stops working altogether. This rare but serious condition leaves patients without adequate red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets—a situation that demands prompt recognition and treatment.

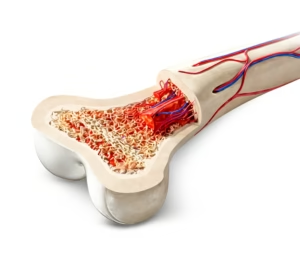

Imagine a factory that suddenly goes quiet. The bone marrow, normally a bustling producer of millions of blood cells daily, becomes nearly empty. Doctors call this hypocellular marrow—under the microscope, instead of seeing crowded, active tissue, they find mostly fat cells and very few blood-forming cells.

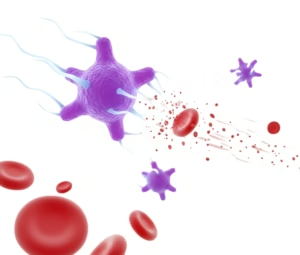

The consequences affect every aspect of health. Too few red blood cells cause severe anaemia—patients experience profound fatigue, breathlessness even with minimal exertion, dizziness, and a pale appearance. Low white blood cell counts leave patients vulnerable to serious infections. Reduced platelet numbers lead to easy bruising, frequent nosebleeds, bleeding gums, and tiny red spots on the skin called petechiae.

Most cases of aplastic anaemia have no identifiable cause, labelled as idiopathic. However, known triggers include certain medications, viral infections (particularly hepatitis), exposure to toxic chemicals like benzene or pesticides, and occasionally autoimmune diseases where the body attacks its own bone marrow stem cells. In India, exposure to pesticides in agricultural communities and use of certain traditional medicines occasionally contribute to cases.

Diagnosis requires careful evaluation. Blood tests reveal low counts across all cell types—a condition called pancytopenia. However, this alone isn’t sufficient for diagnosis. Patients need a bone marrow examination, where doctors extract a small sample to confirm the characteristic emptiness of aplastic anaemia and rule out other conditions like leukaemia or myelodysplastic syndromes.

Severity classification guides treatment. Severe aplastic anaemia, defined by very low blood counts, requires urgent intervention and carries significant risk without treatment. Moderate cases may be watched carefully with supportive care. Very severe aplastic anaemia demands immediate, aggressive therapy.

Treatment depends on age, severity, and donor availability. For younger patients with severe disease who have a matched sibling donor, allogeneic bone marrow transplant offers the best chance for cure—success rates exceed 80-90% in optimal circumstances. The donor’s healthy stem cells repopulate the empty marrow, essentially giving the patient a new blood cell factory.

For older patients or those without suitable donors, immunosuppressive therapy becomes the mainstay. This treatment uses medications like anti-thymocyte globulin and ciclosporin to suppress the immune attack on bone marrow stem cells, allowing them to recover and resume production. About 60-70% of patients respond to immunosuppression, though responses may take several months and sometimes require repeated courses.

Supportive care bridges the gap whilst definitive treatment takes effect. Regular blood transfusions maintain adequate haemoglobin levels and platelet counts. Antibiotics prevent or treat infections. Growth factors like eltrombopag may help stimulate blood cell production.

Living with aplastic anaemia requires vigilance. Patients must watch for signs of infection—fever, cough, unusual symptoms—and seek immediate medical attention. Avoiding activities that risk bleeding or injury becomes essential. However, with appropriate treatment, many patients achieve normal or near-normal blood counts and return to regular activities.

The journey with aplastic anaemia is challenging, but modern treatments have transformed outcomes. What was once a uniformly fatal diagnosis now offers realistic hope for recovery, long-term survival, and good quality of life.